A Munich that talks back

Do you ever wish you could have a conversation with the city you live in? Now, thanks to a combination of the municipally developed digital twin, artificial intelligence, and the work of a local startup, this may soon be possible in Munich. Granted, the questions will have to be quite practical in nature – you won’t be able to ask your city if it feels lonely in emptier months, or what its favourite animal is, at least not for now.

However, you will be able to ask it, for example, whether it’s worthwhile installing solar panels on your home, given the cost of power and the solar potential of your rooftop or balcony. You might even be able to ask it which museums with parks nearby are most convenient to reach via public transport, or which neighbourhood typically has the most job vacancies coming up.

So far, the experiment is just at a proof-of-concept stage. “We gave the startup part of our 3D city model,” explains Markus Mohl, Head of the Competence Centre Digital Twin Munich, “and they combined it with further information from our open data portal and geo portal.” With that, the company developed a ‘live chat’ that engages with the digital model to scan the city and answer user questions.

The AI may identify trees from the aerial images, but you have to prove it's right

— Markus Mohl

Having met initial success, Munich is considering scaling up this AI approach. However, the potential inaccuracy of AI is a worry that the city is anxious to deal with first. “The AI may identify trees from the aerial images, but you have to prove it's right,” Mohl emphasises.

What a digital twin can do

This chat interface is just one novel use case for Munich’s digital twin among many current and potential applications. But just what is a digital twin? You can think of it as a virtual version of the city. This can be visual, a 3D model of the entire terrain and infrastructure. Still, it can also include (or indeed be limited to) connected raw data, such as bus schedules or land zoning information.

In Munich’s case, what comes under the heading of ‘digital twin’ is an intertwined network of dashboards, web viewers, and analytical applications. For instance, users on a web viewer can switch between the current city layout and potential planning scenarios, such as expanded bike lanes. “We can even analyse the quality of the bike lanes visually,” Mohl explains, categorising them by colour based on their adequacy for cyclists.

We can even analyse the quality of the bike lanes visually

— Markus Mohl

Another current use case is a service map for construction sites. Mohl recalls, “A few years ago we had a list with the construction sites from the city administration and a map only from our Public Utilities Department.” Thanks to the digital twin, this list has evolved into a comprehensive, geo-referenced map displaying all construction sites, providing detailed information about their size and scope, as well as how to plan your journey to avoid them.

“We are trying to enable all the information about the construction sites to get a data set that you can use for navigating and routing in the city,” Mohl explains. Munich does not explicitly designate each use case under the ‘digital twin’ moniker. For example, the construction site map is called just that – ‘Construction Site Map’ – despite being a product of the digital twin, focusing on its purpose rather than its origin.

Meeting your needs

For Mohl, the essence of the digital twin is its ability to organise data sharing between a wide variety of stakeholders, including all the departments within the city. “For me, the most important part of the digital twin is communication,” he asserts, “sometimes it's just a platform for talking to each other.”

The most important part of the digital twin is communication

— Markus Mohl

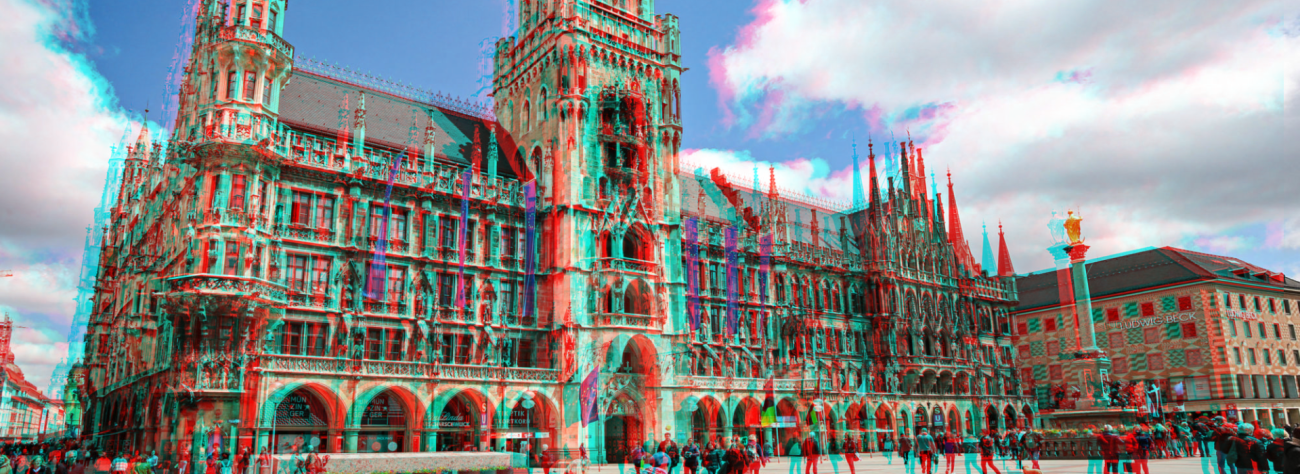

The concept for Munich's digital twin began in 2016 as part of the EU-funded 'Smarter Together' project, in collaboration with the cities of Vienna and Lyon. Mohl recalls, “There was a request from colleagues in the project to present the results in a 3D model.” This request led to the creation of a photorealistic 3D model of Munich, incorporating intelligent streetlights with sensors.

Realising the potential here, Mohl and his team envisioned a more interactive experience. “I said, OK, that's nice, but maybe the data of the sensors should interact with the 3D model, with the city,” Mohl explains. This idea marked the beginning of their digital twin.

In 2018, leaping at an opportunity from a national funding programme in Germany aimed at digitalising traffic systems, Mohl’s team aimed to improve the database for mobility issues in Munich.

Collaboration and communication

This initiative involved extensive workshops with nearly every department in the municipality, including planning, climate and environment protection, mobility and buildings departments.

“It was always the approach of an offer,” Mohl emphasises. They engaged in discussions to understand each department's needs and how the digital twin could support them. The philosophy behind this is that technology itself should never be thought of as the motivation or outcome, but rather as a tool that can enable people in the municipality or its ecosystem to achieve existing tasks more efficiently or build upon new ideas that can help them and the city achieve its existing vision.

For example, one colleague reached out to the digital twin team asking for a photorealistic 3D model of the city. At that time, one did not exist – why not? “We asked you and all your colleagues. Nobody needed it. So we didn't build it,” Mohl responded. Once the need was identified, they learned it was affordable and feasible to create. “Now we are updating it every second year, and our goal is to update the photorealistic 3D model every year because we have a lot of needs in the departments for this data,” Mohl explains.

Nobody needed it. So we didn't build it

— Markus Mohl

It occurred in common discussions with the mobility department that if they had access to an up-to-date street view database, the team could reduce the need to drive out to sites across the city to make decisions about mobility infrastructure. Now, thanks to a mobile mapping campaign, that database is available, and the team can save a lot of time doing their ‘site visits’ from behind their desks. The tools have also generated new datasets, such as comprehensive maps of parking areas, which were requested by various departments.

Justifying the investment in the digital twin is straightforward for Mohl. “The most important thing is to build up a lot of use cases that you are supporting,” he says. Surveys conducted among department colleagues have shown a high level of usage and satisfaction with the Street View data and 3D models. “The results are very good from the digital twin – the payoff is positive at the end for us” Mohl notes with satisfaction.

Collaboration and innovation

As a result of its initial successes and the obvious potential that it offered, the City Council decided that the digital twin would become an ongoing task for Munich's GeodataService, leading to the establishment of the Competence Centre Digital Twin Munich. “The digital twin is not just happening within the project; it's a new, everlasting task,” Mohl states.

The digital twin is not just happening within the project; it's a new, everlasting task

— Markus Mohl

As with any new technology, understanding the full potential of the digital twin requires a lot of stretching of the imagination, and every new use case opens up the potential of many more. To help with this mental exercise, besides discussions with city departments and the private sector, the city is also collaborating with academic institutions like the Technical University of Munich.

A glimpse at Munich through VR

Mohl emphasises, “There's so much scientific work to do, both to learn and show what is possible with a digital representation of the city.” By taking advantage of the mental hothouse that is Munich’s academic ecosystem, the city can encourage innovative ideas.

Standards and sustainability

One big pitfall that many cities investing in new technology have fallen into is failing account sufficiently for the importance of interoperability. Put simply, this means that you invest in a product from one supplier and then find it can’t interact with products from other suppliers.

A basic example would be a city that invests in charging stations for electric bikes from one company, then works with another company to set up an electric bike sharing scheme, only to discover that the bikes they are using aren’t compatible with the existing charging ports. The same kind of issue can occur with software and digital solutions that cannot ‘speak to’ each other.

“We can buy a huge solution from one company, but then we are dependent on this company and unable to interact with colleagues from other cities,” Mohl explains. Ensuring solutions are based on international standards allows for greater interoperability and collaboration across different municipalities.

Having solutions that are interoperable because they apply a common set of standards means that projects are more sustainable, more viable in the long run. Munich puts a lot of effort into ensuring that this is the case, even if this requires more time and resources in the short run. “We don't want to go the quickest way,” Mohl asserts, as the goal is for cities to give each other mutual support by building solutions that can be used and shared.

It's important to be sovereign as a city and data sovereign

— Markus Mohl

Building their own solutions rather than relying on those of major tech companies like Google Street View is important for Munich. “It's important to be sovereign as a city and data sovereign,” Mohl notes. Munich's commitment to open data remains strong, with most geo-data available to the public. “Almost every data set we have at the GeodataService is open data,” Mohl emphasizes.

This is not to say that there is any tension between the services that Google offers and those offered by the city – all the city’s open data is available to the tech giants too. As Mohl points out, the more accurate the tools of Google or Apple, the safer for residents of Munich, and even he uses Google Maps to find his way around sometimes.

Data collection and privacy

The primary data sources for the digital twin are the city's detailed urban geo data in both 2D and 3D formats. “We have all the vegetation data, bike lanes, pedestrian areas, and car traffic zones,” Mohl explains. Data collection involves aerial imaging from aeroplanes and mobile mapping campaigns by camera-laden vehicles driving around the streets.

You can see that some residents might be concerned about what could appear to be extraordinary levels of surveillance, and protecting the privacy of the people in Munich is a key concern for the city. For this reason, all images anonymised to protect individual identities. “The service provider is anonymising the images so you cannot find any signs of the cars or faces,” Mohl explains. And it’s not just faces – all the city’s imaging is processed to blur the entire bodies of anyone caught on the cameras so that not even a visible tattoo or characteristic clothing could potentially be used to identify them.

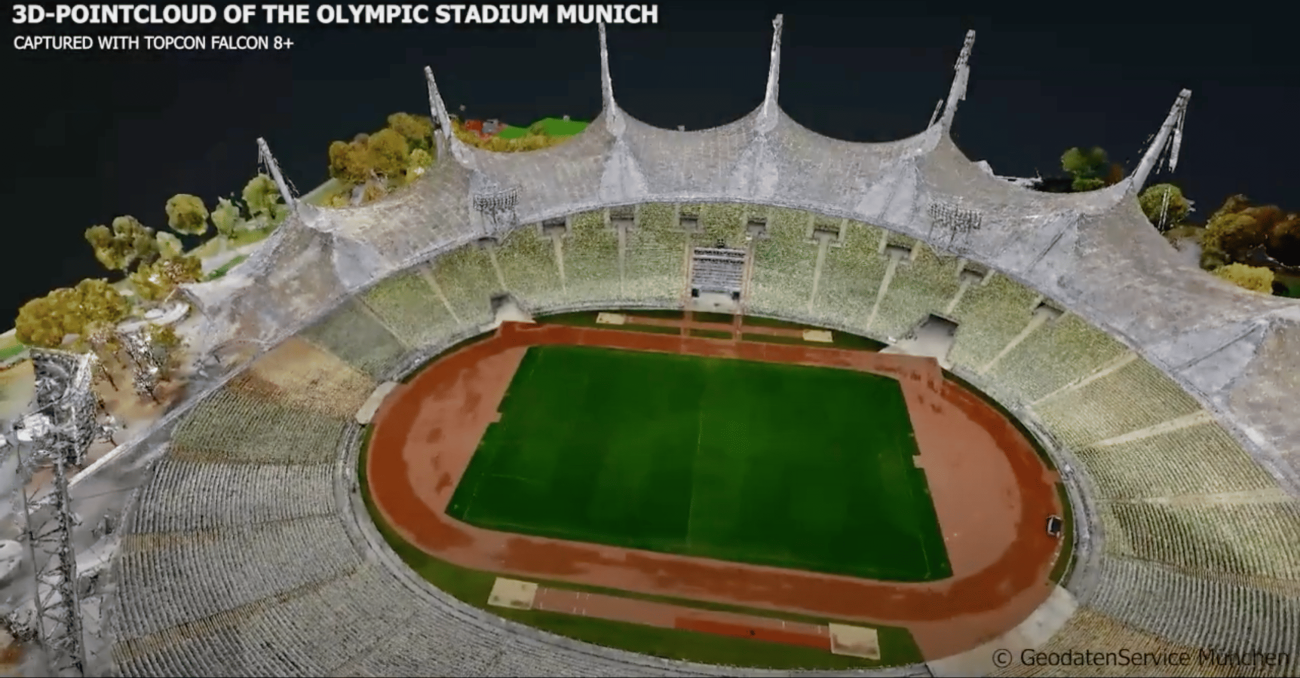

Munich employs drones to gather detailed information in specific areas, complementing aerial images captured by planes. Mohl highlights a project involving the Olympic Stadium: “We had our own campaign to take images of the Olympic Stadium to have more detailed information so we can identify every seat.” Drones are also used annually to create 3D models of the Oktoberfest for the fire department, aiding in the comparison with rescue plans and enhancing security measures.

Traveling harder path

“When I started to work for the city of Munich,” Mohl recalls, a colleague once told him, “Working for the local government, you can move an incredible amount for your city, but you do not have to.” This continued to resonate with Mohl and guided him on deciding to start the digital twin project in 2018.

Sometimes you have 10 hours or more a day, but for me, it's worth it

— Markus Mohl

He recounts, “My colleague and I asked each other, should we start it or should we not, because we already have a lot of work.” Ultimately, they decided to proceed, recognising the opportunity to innovate and support Munich's development. “Now it's a really huge thing, and for us in Munich, the digital twin is the digital infrastructure of the climate-neutral city.”

Mohl acknowledges that the workload involved in the digital twin project is certainly quite steep: “It's a harder path, it’s a lot to do, and sometimes you have 10 hours or more a day, but for me, it's worth it,” he says. The shared commitment to innovation and improvement, and seeing the concrete benefits for his colleagues and the people in his city makes the effort worthwhile for Mohl and his team – perhaps when they can be digitally cloned too, they’ll be able to sign off early every now and then.